A Tale of a Tea Merchant Token

By Denis Richard, Coin Photography Studio

October 29, 2024

7-minute read

1793 Manchester Promissory Halfpenny

In the late 18th century, shops lined the busy streets of Manchester, England, offering a wide range of goods. Among them were the haberdasheries, apothecaries, and grocers, - or spice merchants - who specialized in selling spices, sugar, honey, tea, coffee, and tobacco alongside drugs and medicinal products. Typically, these items were sold by weight in what was commonly referred to as a "grocery store." They prided themselves on their selection of coffee and tea and were known to keep a kettle in store to offer samples to potential customers. It's a tradition we still see today in modern markets.

During the early industrial age, tea and exotic spices arrived in England from across the empire. Ironically, it was often easier to find these items in stores than it was to find the coins needed to purchase them.

Before the widespread adoption of paper currency, gold and silver coins were rare commodities, but copper coins were almost impossible to come by. Most coins in circulation were either clipped or counterfeit, vastly exceeding the number of government-issued coins. Fewer than one in ten coins even resembled the official regal currency.

The reasons for this predicament are numerous, but in this era of coinage chaos, trade tokens like our featured halfpenny became the people's currency. Issued by merchants, tradesmen, and individuals, they supplemented the lack of official coins and kept the economy afloat.

Our featured token, a 1793 Manchester Promissory Halfpenny, was struck for John Fielding, a grocer and tea merchant who conducted his business at 27 Withygrove, Manchester, England. As a grocer, John Fielding belonged to the grocer's guild, officially known as The Worshipful Company of Grocers. Established in 1345, the Grocers were a longstanding and powerful guild. Given this connection, finding the guild's coat of arms on the obverse of his token is unsurprising.

Obverse above. A simplified version of the Coat of Arms of the Worshipful Company of Grocers. Below, is the official CoA.

The token artists, Arnold and Roger Dixon, did a commendable job replicating it. We see a shield flanked by griffins on each side, crowned by a camel carrying what looks like a saddle but is actually bags of spices on its back. Below this ensemble is a banner bearing the inscription "GOD GRANT GRACE," complemented by the legend: "MANCHESTER PROMISSORY HALFPENNY 1793."

The vivid blues and red of the official coat of arms, shown right, are serendipitously reflected in the coin's tonal hues.

The shield is adorned with cloves—four above and two below the chevron. In 16th—and 17th-century Europe, pepper, cloves, and nutmeg were among the most precious items, worth more than their weight in gold. Interestingly, the Grocers guild originated from a group of 22 Pepperers, individuals who traded in pepper. These Pepperers, along with Spicers and Grocers, are the ancestors of today's pharmacies.

Despite its name, the Manchester Halfpenny was not minted in Manchester, but 80 miles south in Birmingham, by William Lutwyche (1754-1801), who transitioned from toymaking to becoming a prolific and somewhat notorious manufacturer of tokens. By the time Lutwyche struck this halfpenny, Birmingham had already gained notoriety as a hub for producing counterfeit coins, especially copper ones. This reputation prompted R.E. Raspe to mention in his "Descriptive Catalogue of Gems.." (Edinburgh, 1791) that the 'Brummagem ha'pence' were produced by 'shabby, dishonest button-makers in the dark lanes of Birmingham."

However, not all of Birmingham's manufacturers were making counterfeits. Many reputable firms, such as Matthew Boulton's Soho Mint, produced official coinage using techniques surpassing the Royal Mint.

The other side of the coin

The reverse side of the token presents a bit of a puzzle—not in its identity, but in the purpose of some of its elements. The legend reads: "PAYABLE AT IN. FIELDING'S GROCER & TEA DEALER." This fits with how tokens have been historically used to boost local businesses, suggesting that Fielding purchased it as an advertising tool.

The late-18th century version of the genuine EIC trademark.

In the center of the token is the bale mark of the East India Company (EIC). Today, we'd call it their logo. It's a heart-shaped symbol, representing 'good luck,' crowned by the number four, which symbolizes the Agnus Dei or 'Lamb of God.' The emblem incorporates the initials of the Company, V E I C (United East India Company). Like the Romans, the letter U is represented by a V.

Including the EIC's bale mark on the token is peculiar and raises many questions. The EIC was an enormous trading company, which at this time had a virtual monopoly on all English trade with the East Indies. Why did a small-town grocer in Manchester have the EIC logo on its token? Did he purchase their goods? Was it included for brand recognition?

It's plausible the EIC bale mark originated from Lutwyche, who frequently repurposed existing dies in his collection to produce a variety of mules and was known for crafting numerous questionable issues. Was Lutwyche striking coins for the EIC?

Renowned numismatist Richard G. Doty states that in 1791 and 1794, the years when this token was struck, Boulton's Soho Mint was actively producing millions of copper coins for the EIC, many with the bale mark on the reverse. It seems unlikely that a company of Lutwyche's size and reputation would have also been engaged in minting coins for them, so it's possible that Lutwyche obtained the dies for his unofficial use.

I have nothing but speculation, but if you, dear reader, have any insight or theories on including the EIC bale mark on Fielding's token, please do share and continue the discussion in the comments below.

You need how many?

Manufacturers like William Lutwyche played a pivotal role in the evolution of token production, broadening its driving forces to 'supply' and 'demand.' This transformation turned tokens into a marketed commodity instead of merely a commissioned item.

Lutwyche aimed at the rural market segment, close to the sources of raw materials or waterpower, concentrating his sales efforts on tradesmen and shopkeepers in provincial areas like Manchester. Perhaps a savvy merchant, John Fielding, might have sought out tokens to boost his business visibility or a travelling salesman from Lutwyche's visited his shop. Birmingham's toy manufacturers, even leading medallion creators such as Matthew Boulton, had long employed travelling salesmen to promote their business, and Lutwyche probably followed a comparable strategy, if more modestly.

According to historical records, this halfpenny token was produced in enormous quantities for its time and place, with a total issuance valued at £2,300. To comprehend the volume of coins this represents, consider that with two halfpence per pence, 12 pence per shilling, and 20 shillings per pound, £2,300 could purchase more than 1.1 million halfpenny tokens. Manchester was home to just 18,560 families, and at a time when people earned only a few shillings per week, this was quite a fortune.

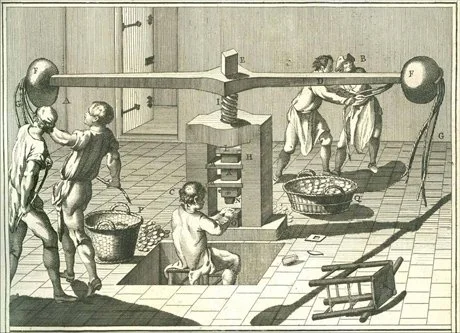

Lutwyche produced a vast array of tokens in relatively limited quantities. Still, his production output of more than 65 tons of "legitimate provincial coins" was surpassed only by Thomas Williams, the consortium of Westwood and Hancock, and Matthew Boulton's Soho Mint. The fact that Lutwyche lacked steam-powered coin presses makes this even more remarkable, meaning a screw press, like the one shown at right, produced the coin featured here.

What does a million pennies look like?

In Ontario Canada, John Reyes and his wife stumbled upon 1 million copper pennies while cleaning out her father’s 1900s-era home.

(photo by John Reyes)

It remains a mystery why Fielding ordered such a large quantity of tokens. The £2,300 cost would be too great for a single shopkeeper. This fact led David W. Dykes, in his book "Coinage and Currency of the Eighteenth-Century – The Provincial Coinage," to propose that Fielding spearheaded a consortium of trade members. This group absorbed the costs, making it more economical to provide tokens for their collective use than it would have been individually.

We may assume Fielding's plan to hand out promissory tokens that could only be used at his store was intended to build customer loyalty and motivate people to come back and buy more. However, the notion of 'promissory' was interpreted quite broadly by numerous issuers, and many viewed issuing tokens mainly as opportunities for speculative gain, content with the idea that once their halfpennies were distributed among the public, they would never have to redeem them. This strategy remains effective today, with up to 10% of gift cards going unredeemed, translating into a profitable revenue stream for businesses.

Today, after 221 years, of the over one million tokens minted, how many remain is anyone's guess. Some undoubtedly lie buried in old gardens and building sites, while others may still be hidden away in collections or treasured by descendants of those who originally received them. Most are likely melted. But many of those that survive in collectors' hands, like the coin pictured here, are well worn, evidence of the extensive circulation they received.

The last interesting feature of this token is it has a die clip or a defective planchet, as seen in the images below. This little nick adds character to the coin, making it slightly less valuable to collectors. Ces't la vie.

The contribution of grocers, often overlooked, played a crucial role in people's daily lives in 18th-century England. This grocer's token has survived over two centuries, outliving its initial use and being passed down through generations. Still, there remain many questions. Who was John Fielding? During his time, seven individuals with the same name were interred in the Manchester area, and it is unclear which one of them issued our token. What drove him to issue these tokens, and how successful was his plan? We'll likely never know the answers, but pondering and exploring the possibilities is fascinating.

I've never enjoyed drinking tea, but I do enjoy having this tea merchant token in my collection.

The Photography

Denis Richard photographed this coin in its raw state using a hybrid axial lighting system developed by Coin Photography Studio. It is easy to bring out the beautiful colours of this copper coin, or any coin, with this system.

Coin Photography Studio uses this same system to photograph coins for collectors and dealers. They believe in providing high-quality images that accurately depict the coins they represent.

A Final Thought

Thank you for reading this blog post! I hope you found it informative and enjoyable.

If you're interested in similar topics, be sure to check out our other posts on numismatic subjects. From coin history to coin photography, we have lots to offer.

Don't forget to leave a comment below with your thoughts and feedback. We love hearing from our readers and it helps us improve our content.

Thank you again for your support and we hope to see you back here soon! Happy collecting!

READ MORE:

Merchant tokens like the Manchester Promissorry Halfpenny are called Conder tokens, named in honour of James Conder (1761–1823), an esteemed English businessman and numismatist. He was among the pioneers in cataloguing the 18th-century independently minted copper trade coinage, which frequently carries his name today, known as Conder Tokens, though in England are generally referred to as “provincial tokens.” His book, titled "An Arrangement of Provincial Coins, Tokens, and Medalets Issued in Great Britain, Ireland, and the Colonies, within the Last Twenty Years, from the Farthing to the Penny Size," was published in 1798. His work remained the go-to resource for nearly 100 years.

Forty years after he died, his house located at the intersection of Old Buttermarket and White Hart Lane was torn down. During the demolition, a stash of Anglo-Saxon coins was found buried ten feet under the doorstep.

Coin references:

British and Irish Tradesmen and their Copper Tokens of 1787-1804

Jon D. Lusk

Some Reflections on Provincial Coinages 1787-1797

David W Dykes

http://www.chiefacoins.com/Database/Countries/East_India_Company.htm